If blackleg levels are on the rise in your canola field, think about adjusting your tactics for managing this yield-limiting disease.

Blackleg-resistant canola varieties are an excellent tool for managing this potentially serious disease, but we need to take care of them.

“If we deploy the same genetic resistance over and over again, then we put a lot of pressure on that genetic resistance and it could break,” says Michael Harding, a plant pathologist with Alberta Agriculture and Forestry.

That’s the reason researchers are monitoring this fungal pathogen and its races in Alberta and the rest of Western Canada. And that’s why growers need to monitor their own canola fields.

“If you’re growing canola every year or every second year, and you are starting to see an increase in blackleg over time, that is an indicator the races within your field are adapting to overcome the resistance deployed,” says Justine Cornelsen, the blackleg lead for the Canola Council of Canada (CCC). Rising blackleg levels are a reminder to reach into your toolbox for some of your other tools like changing to a canola variety with a different blackleg resistance package and/or extending your crop rotation.

Cornelsen explains two fungal pathogens — Leptosphaeria maculans and Leptosphaeria biglobosa— can cause blackleg in canola. Leptosphaeria maculans is the major concern on the Prairies. Canola residues infected with this fungus release spores that can infect susceptible canola plants as early as the cotyledon stage.

The infection spreads down from the foliage to the base of the stem. The disease can result in stem cankering, lodging and major yield losses, especially if the infection begins when the crop is very young.

A Look at the Alberta Situation

Harding has been leading Alberta’s blackleg surveys since 2015. He says the province’s blackleg surveys have been sporadic over the past few decades with surveys conducted for a couple of years, then no surveys for a few years, then another survey for a year, and so on. A key issue was whether the person responsible for monitoring canola diseases in Alberta had enough funding in any given year to cover the survey’s manpower and diagnostic costs.

“I was in the same boat; I had some limited resources, but not necessarily enough to do a canola disease survey every single year,” he says. Thus, Harding and his group are taking a different approach. “We are coordinating the survey, but we ask for volunteers — people interested in canola disease could help out by surveying a few fields.”

In 2015, Harding’s group partnered with agricultural fieldmen in counties across the province. In 2016 and 2017, they received funding from the Alberta Crop Industry Development Fund and partnered with agricultural research associations in the Agricultural Research and Extension Council of Alberta (ARECA). Last year, and in 2018, they partnered with the agricultural fieldmen again. These surveys include blackleg, sclerotinia and clubroot.

“This has been a really big step forward for us in Alberta to have a consistent, long-term, annual disease survey in canola,” says Harding. “And it is thanks to partnering with groups like the agricultural fieldmen and ARECA. We’re going to continue with this partnering approach.”

They try to survey about one per cent of the canola fields in each county, collecting data on blackleg prevalence, incidence and severity. The table below summarizes the results from the 2015 to 2018 surveys. The blackleg levels were a little higher in 2016 due to wet conditions that favoured the disease.

Results from Alberta Blackleg Surveys, 2015 to 2018

| Parameter | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 |

| Number of fields surveyed | 208 | 480 | 421 | 339 |

| Prevalence: percentage of surveyed fields that have blackleg symptoms | 70.7% | 90% | 82.2% | 80.5% |

| Incidence: percentage of stems with blackleg symptoms | 13.1% | 21.2% | 14.0% | 13.25% |

| Severity: rated on a scale from 0 (no disease) to 5 (completely diseased) | 0.39 | 0.42 | 0.26 | 0.24 |

Courtesy of Michael Harding, Alberta Agriculture and Forestry

Harding summarizes. “Overall, our surveys show blackleg is widespread in the province, but we generally only see 10 to 20 per cent of the plants with symptoms, and the severity on average is very low in most fields — less than one out of five. Meaning, the resistance in our canola varieties is working very effectively.”

Harding states the 2019 blackleg results could be quite different in various areas of the province. “In 2019, some parts of Alberta had almost no rain, and in other parts it wouldn’t stop raining. For southern Alberta, I’m guessing that the 2019 blackleg numbers will be quite similar to those in 2017 and 2018. But in the central part of the province, where they essentially had rain all season long, we could have much higher levels.”

To try to draw more information from the survey data, Harding and his group have started conducting a hot spot analysis. “The data points in the survey have a precise GPS location attached to them so we can map them. One of the tools in the mapping software can look around each individual point that has a high severity to see how many points nearby also have a high severity. If it reaches a certain threshold, it will tell you there might be a little hot spot there,” he explains.

“This analysis is one way we can distil down an enormous amount of survey data and say, ‘here are some areas we may need to look at a little closer.’”

They first conducted the hot spot analysis in 2018.

“We found a few spots with a little higher severity and maybe a little higher incidence. We don’t yet know what causes the hot spots, whether they might be due perhaps to the appearance of a new virulent race that is overcoming the resistance in our varieties, or maybe the local weather conditions pushed the severity a little higher.”

The 2019 data could help to shed some light on the cause of the hot spots.

“Since a significant part of the province had lots and lots of precipitation and another pretty significant area had almost no rain, that will help us to sort out what the biggest driver is of these hot spots: is it the weather, or is it something else like the crop rotation history or new blackleg races? After we do this analysis for a number of years in a row, we should be able to say with some certainty what is going on.”

Blackleg infection spreads down to the base of the canola stem, causing black cankering and yield loss. Photo credit: Justine Cornelsen, Canola Council of Canada

Three Key BMPs for Managing Blackleg

“Our top three best management practices for blackleg really come down to some of the basics for effective disease management,” says Cornelsen.

“Scouting is No.1. Monitoring is key to knowing if you have an issue with your resistant variety.”

She recommends rating the blackleg levels in your canola fields each year, especially if you are using a short rotation and if you think you may have a blackleg issue in some fields.

“The best time for blackleg scouting to help make decisions for future years is at 60 per cent seed colour change, right around when you would typically swath the crop,” says Cornelsen.

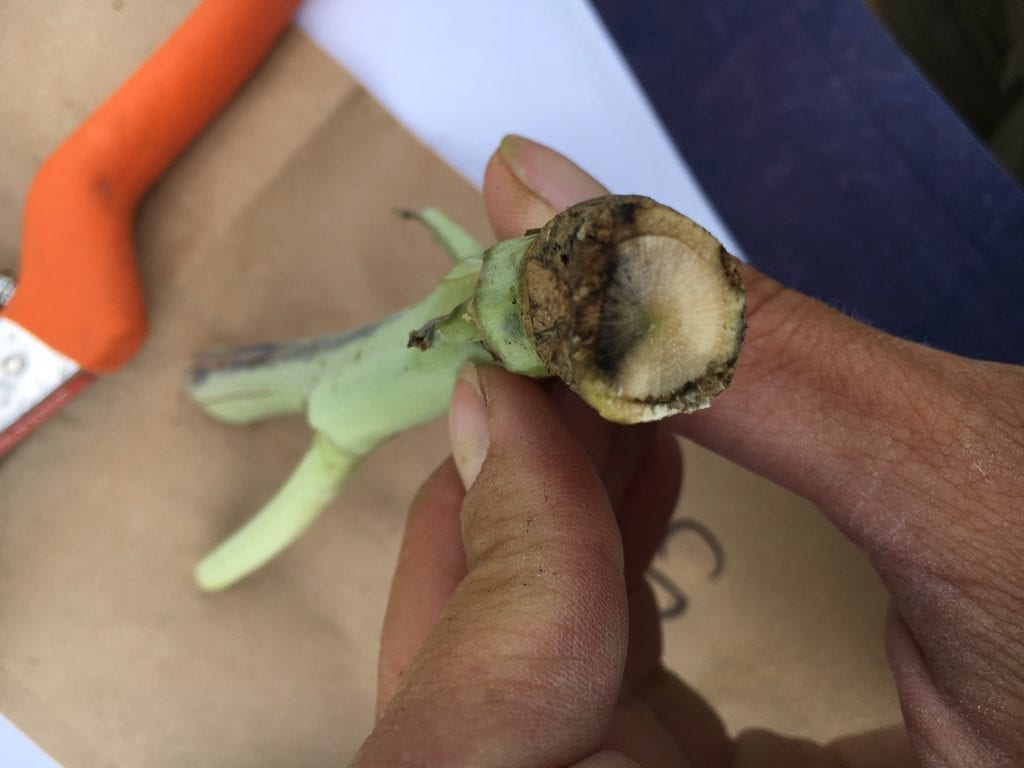

“You go into the field, pull up the plants, cut through the top of the root, and rate your plants on that 0 to 5 scale, with 0 being a clean, healthy plant that has no sign of black tissue in the cross section, and 5 is showing complete internal blackening.” Sampling instructions and the rating chart are available on the CCC website.

“You can use this severity rating to determine how much yield you have potentially lost due to blackleg, if you were above or below the provincial average [for the disease], and whether the disease level has been increasing over time in that field,” she says.

“That information helps you to make decisions the next time you grow canola in that field. If the disease levels are rising, then maybe you need a varietal change, or maybe the disease is so severe you need to think about extending your crop rotation on that particular field.”

Crop rotation is the second of the CCC’s top three best management practices (BMPs).

“Blackleg is very easily managed with an extended rotation,” Cornelsen emphasizes. “If you can move to growing canola once out of three years, you allow the old residue which houses the pathogen to die down in the field naturally. That will minimize the risk of the field having severe blackleg.”

“When blackleg showed up as a real force to be reckoned with in Alberta back in the 1970s and 1980s, it was managed with crop rotation. The one-in-four rotation with canola really came about because of blackleg — the fungus does not survive very long in the soil unless it has host tissue,” says Harding. “The lower part of the canola stem persists the longest; it is kind of a woody tissue that survives for two or three years. But once that breaks down, there is nothing left for the blackleg fungus to survive on, so it dies.

The blackleg fungus can also be seed-borne, but close to 100 per cent of the canola seed purchased has been cleaned and treated with a fungicide to prevent any seed-borne issues with blackleg, he adds.

The third key BMP is using blackleg-resistant varieties.

“In Canada, all commercially available varieties are rated as resistant or moderately resistant to blackleg. We are all doing this BMP already,” says Cornelsen. “The next level is stewarding the varieties better.”

Rotate Resistance Genes

In addition to the big three BMPs, one of the secondary practices on the CCC’s blackleg BMP list is rotation of resistance genetics.

Blackleg resistance relies on two types of resistance: major gene resistance, which is very effective, but specific to particular blackleg races; and quantitative resistance, which involves multiple genes that each contribute a small amount to the plant’s overall ability to resist the disease at stem cankering.

In major gene resistance, the resistance gene in the plant has to match up with the corresponding avirulent gene in the pathogen. For example, the resistance gene Rlm2 is only effective against races with the avirulence gene Avrlm2.

Since the 1990s, resistant canola varieties with the same one or two major genes have been widely used on the Prairies. That has put selection pressure on the pathogen to shift toward other races. Research by Gary Peng at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in Saskatoon and others shows some Avrlm genes have become less common and others have become more common over the past couple of decades in Western Canada.

Each year, as Harding’s group assesses blackleg severity in the stems collected in the Alberta survey, whenever they see a stem with blackleg symptoms, they cut off a one-inch piece and send it to Peng. Peng is currently monitoring the blackleg races in Western Canada. His group isolates the blackleg fungus from the samples and determines which avirulence genes are present. Harding also passes along the hot spot analysis from the Alberta survey in case that helps hone in on some areas that might be a concern for development of new blackleg races.

Peng’s research also suggests many canola cultivars probably have both major gene and quantitative resistance. Even if the pathogen’s population shifts to overcome a race-specific major gene, most cultivars have non-race-specific quantitative resistance that slows the pathogen’s spread in the plant and reduces the disease’s impacts on yields.

Canada now has a voluntary labelling system that identifies the major resistance genes in canola cultivars. At present, DeKalb, Canterra Seeds, Brett Young and Cargill are using this new labelling system.

“The old recommendation was just to switch your variety [if you noticed increasing problems with blackleg in a field]. You could have unknowingly switched to a variety that would actually be worse for that field,” explains Cornelsen. “Now that we’ve got more information, rotation of resistance genes has become a new best management practice.”

Growers and agronomists can submit canola stubble samples to a diagnostic lab to have blackleg races identified. The pathogen is very diverse, so most fields will likely have multiple races. The idea is to choose a canola variety with resistance to the main avirulence genes in the field, if such a variety is available.

“Right now, we have four major genes identified (some varieties are identifying a fifth unknown gene) in Canadian canola varieties. Looking at our blackleg race profile in Western Canada, there would be the potential to adopt an Rlm7 resistance gene in our varieties, to match up with Avrlm7, which is becoming increasingly common here,” says Cornelsen.

She is hopeful additional major genes will become available in Canadian canola varieties in the coming years. “A lot of the life sciences companies in Canada have access to materials with other resistance genes that are deployed in other countries. Also, researchers with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada at Saskatoon have identified some new resistance genes, which will be available to the Canadian market. But it takes time — when you’re introducing a new trait or gene it can take upwards of 10 years to get the new varieties out.”

To evaluate blackleg severity, clip the plant at the top of the root and assess the degree of infection visible in the cross section. Photo credit: Justine Cornelsen, Canola Council of Canada

New Fungicide Options on the Way

“Fungicides are not commonly used for controlling blackleg on the Prairies at present, mainly because producers don’t necessarily see a return on investment within the application year. That is probably because we are missing the critical window of infection,” explains Cornelsen.

“Just in the last year or so, we have really dialled in on when the critical stage for infection occurs for blackleg on the Prairies. It’s the cotyledon to two-leaf stage. The plants infected at that very early stage will be the ones that suffer the greatest yield loss or may not even make it to harvest. If we can protect the plants at that early stage, we will really minimize the severity of the disease in some fields.”

Infection at this really early stage is not unusual. “The infected residue only needs a little moisture and temperatures around 15 to 16 C to start producing spores. [Often in a warm spring,] the pathogen is already releasing spores when the canola cotyledons are popping out of the ground,” Cornelsen says.

She explains the foliar fungicides registered for blackleg in canola are labelled for the two- to six-leaf stage, by which time the plants could already be infected. And even if the fungicides were registered for the cotyledon stage, a foliar application at that timing would likely be impractical. “Growers are often busy with planting when canola is at the cotyledon stage. And it’s tough to wrap your head around the idea of spraying at the cotyledon stage because you would be spraying bare ground.”

However, new seed treatments are on the way. “Within the next few years, we are going to have some new seed treatments coming on the market that can protect the plant at that critical window from the cotyledon to two-leaf stage. I think the new seed treatments will prolong the use of some of the genetics in our blackleg-resistant varieties.”

One of these new products is Syngenta’s Saltro. “We’re excited about what Saltro fungicide seed treatment will bring to the management of airborne blackleg,” says Scott Ewert, head of Seedcare with Syngenta Canada. He explains Saltro will provide a new tool as part of an integrated disease management approach, together with crop rotation and genetic resistance, to manage blackleg in canola, minimize yield loss associated with this disease and support the longevity of canola seed genetics.

This seed treatment contains a new active ingredient, adepidyn, which is an SDHI mode of action. Syngenta anticipates registration of Saltro seed treatment in time for use in the 2021 growing season. “What’s unique about Saltro is it will provide protection against airborne blackleg at canola emergence through what we now know to be a critical infection period for the disease, the cotyledon stage,” says Ewert.

“With blackleg management, we can’t rely on just one tool,” says Cornelsen. “I know we put our resistant cultivars up on a pedestal, but we’ve got to look at prolonging their longevity and using all of our management tools. Crop rotation and scouting are really key pieces to managing this disease.”