In the cannabis sphere, genetics is only the beginning as breeders work to understand the plant and create the next generation of seed.

Greg Baute has a problem. It’s one that many breeders of other major crop kinds wish they had.

“There’s too much genetic diversity in cannabis right now. If you have seeds, because there are no inbred lines, they’re going to be very heterogeneous — all over the place — and in production, you’ll see a range of plant sizes with varying cannabinoid levels. Nothing at all like we see in row crops,” says the director of the under-construction Cannabis Innovation Centre (CIC) based in the Comox Valley of British Columbia.

“For example, the agronomics of corn production all look mostly the same. That’s not the case in cannabis at all. That’s a good problem to have in breeding, but it’s still a problem. We’re just beginning to figure out what diversity we want and take our material in that direction.”

Baute, 33, left a job with Monsanto working in vegetable seed to helm the CIC construction project being undertaken by Aurora Cannabis subsidiary Anandia. He comes from an agricultural family, his parents having had founded the Ontario-based hybrid corn seed company Maizex Seeds.

For Baute, the legalization of recreational cannabis in October 2018 opened the door to a fascinating new world of breeding discoveries, a world in which breeders are only beginning to unlock the mysteries of a plant they have never before been able to properly research.

“Even in crops that are completely neglected, there’s usually a gene bank curated by a professional. You’ll know where a sample was collected and when. In cannabis, we have nothing like that. It’s a random grab bag of germplasm. The Golden Age of cannabis breeding is literally just beginning.”

Anandia was founded in 2013 by Jonathan Page and John Coleman who saw the need to support the expanding cannabis industry with better science on testing, genetics, and other technical needs.

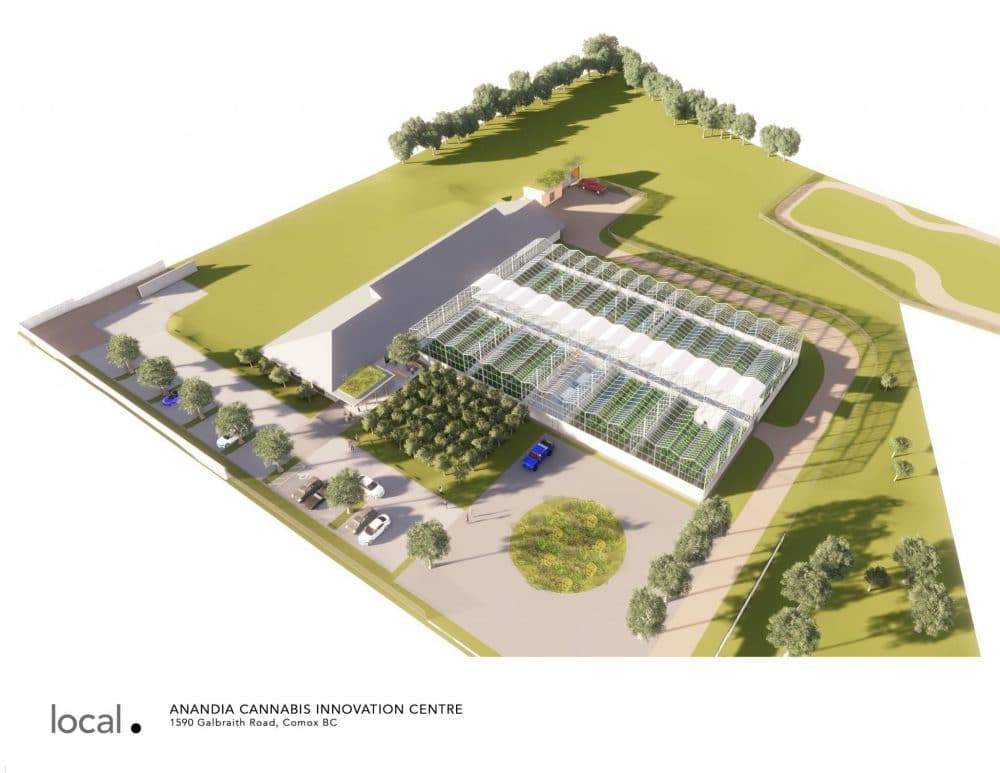

The Cannabis Innovation Centre will begin operation in the fall of 2019 and will serve as the new headquarters for Aurora’s plant breeding work. The first phase of the Comox project will consist of a 21,000-square-foot greenhouse and a 10,500 square-foot research building that will have offices, lab space, meeting rooms, and also house all the mechanical and electrical systems that support the greenhouse.

Most agricultural crops have had decades (if not centuries) of breeding to develop beneficial traits. Cannabis hasn’t received the same attention by plant biologists and plant breeders because of the historical difficulties in obtaining the appropriate licences. Aurora will be using traditional plant breeding techniques to develop new cultivars that have desirable chemistry, disease resistance, and/or traits that improve industrial cultivation practices.

As far as cannabis seed goes, that last point is key.

As Canada will allow the sale of edible cannabis products starting in December 2019, Baute says varieties that lend themselves to the production of edibles and other products which use cannabis extracts (as opposed to varieties grown for the flowers themselves) represent a major untapped market researchers like him are just beginning to select for.

“If you’re making an edible, for example, it’s still the flower you’re after, but you don’t care what it looks or smells like. That relieves some of the selection pressure as a breeder. You only need to talk to a few producers to know where most of the costs in breeding go, and right now that’s for cloning. It’s labour intensive,” Baute says.

“There are lots of annual crops that can be propagated clonally, but no one does that because seed works so much better. Annual plants have evolved to grow from seed. Everyone is thinking the same thing — the question is how fast we get there. How fast can we make seed that has good enough quality and the desired uniformity that we can use those seeds for large-scale production?”

Trading Scissors for Combines

Right now, cannabis harvesting in North America looks very different from other crop kinds, Baute notes. In U.S. states where cannabis is legal, he says you can already see cannabis production from seed at some scale and producers — especially those harvesting cannabis varieties for their CBD as opposed to THC — are struggling to stay cost competitive.

“They’re harvesting plants with a chainsaw and throwing them through a wood chipper and dragging them to a corn silo to dry. In Canada, for high-end flower, you’re trimming with a pair of scissors and inspecting each one by hand and hand packaging it. For a combine-scale operation, you need seed.”

One of the pioneers of high-CBD cannabis varieties in the United States is John McKay of New West Genetics (NWG), which has created the first certified American hemp seed. McKay is the director of genetics for New West and a professor in the Bioagricultural Sciences and Pest Management department at Colorado State University.

The company was founded five years ago when the United States first legalized hemp research and is focused on creating high-yielding, combine harvestable hemp varieties that are adapted to U.S. and newly-legal production environments. NWG announced in March of this year that its proprietary hemp varieties, NWG-ELITE and NWG-RELY, placed in the top of dual-purpose (fibre and grain) trials conducted last summer at the University of Kentucky.

McKay and the NWG team made pilgrimages to Europe and Canada to see what other countries were doing to breed new varieties of hemp, but he says New West’s products are uniquely American.

“It was useful to understand the agronomy angle and see how to breed to maximize yield under those production systems, but there simply hasn’t been enough dollars put into hemp breeding in Canada or Europe for us to gain a great deal of breeding knowledge from them,” McKay says.

“In the U.S., big seed companies spend billions a year on cutting-edge breeding approaches but only invest heavily in crops that are planted on at least 30 million acres. In Europe, it’s largely federal legacy breeding programs that aren’t well funded that have developed and maintained open pollinated grain and fibre varieties over time. We’re actually learning more from other domesticated species where serious technology has been applied and then we’re applying that to hemp.”

For McKay and New West Genetics, one of the best places to look to learn how to breed hemp actually has nothing to do with plant breeding at all.

“You basically have to look to cattle to find how to run an intensive breeding program for a species like cannabis that has both male and female plants,- or are diecious” he adds. “There are some fruit trees that are diecious, but they generally don’t have high-tech breeding programs attached to them. We’re having to look more to the animal model because plant breeders aren’t typically familiar with diecious plants.”

In addition to fibre and grain, NWG is also breeding for large-scale production of non-THC cannabinoids.

With CBD becoming a hot commodity for its use in tinctures, ointments and more, NWG is carving a niche for itself in a market previously untapped.

“Given our regulatory system, right now people are using clonal propagation and manual labour to harvest hemp for CBD production. Where we come in is having these varieties optimized for mechanical processing, but still have good CBD yields on a per dry weight basis and superior yields on an acre basis,” says McKay.

Genetics is Just the Start

Despite the promise held by new varieties of hemp that promise higher CBD levels, Jan Slaski of InnoTech Alberta has a few words of warning.

Over the last 17 years, Slaski has been leading research aimed at the introduction and breeding of hemp varieties that suit the needs of the fibre and food industries on the Prairies. To fully realize potential residing within the hemp plant and to ensure whole crop utilization, he assembled a breeding program that includes three domains: breeding and agronomy, fibre processing and product development.

According to Slaski, the excitement surrounding CBD and other cannabinoids produced in the hemp plant will be tempered as producers learn more about just how complicated the process can be when it comes to getting a quality product for processing.

“I get five to eight calls every day from people asking how they can make money on CBD and claiming to have access to high-CBD lines. The fact is, genetics is only one of three factors when it comes to successful CBD production,” he says.

Currently, no varieties of high-CBD hemp are registered to be grown in Canada. Because hemp is simply cannabis that is bred to contain low THC levels (by law, it must contain no more than 0.3 percent THC), hemp producers in Canada looking to sell their product for CBD extraction must use hemp varieties that contain comparatively low levels of CBD, generally in the two percent range.

“For years, very few breeding programs in the world focused on improving CBD levels in industrial hemp varieties. They looked primarily at early maturity, short stature, something that suited the needs of grain growers,” Slaski says.

“I’ve been regularly approached by people claiming to have access to lines with 10 to 15 percent CBD. Health Canada is very firm on what needs to be done to get high-CBD varieties on the list of approved cultivars — three years of field trials in Canada and no more than 0.3 percent THC.”

In other words, it’s going to be a little while before high-CBD hemp varieties are approved in Canada.

Until then, Slaski says producers hoping to capitalize on the CBD from hemp have to think hard about a variety of factors, genetics being just one.

“Growing conditions are very important. Environment influences CBD levels in industrial hemp,” he says.

The other factor is crop management, something Slaski says is often forgotten in the rush to extract CBD from hemp.

“You can lose up to 80 percent if you don’t know what you’re doing, like drying it excessively or not handling it with care.

“High-CBD hemp is grown in the U.S. in an orchard style. Each plant is harvested by hand and then handled and dried in a shed. Everything is manual. Such farming practices are useless at a large commercial scale in Canada due to our large number of acres,” he says.

Greg Baute envisions a future in which new varieties of cannabis are available for just such a purpose.

“The question is how high can you push CBD content without going over that threshold of 0.3 percent THC,” Baute says.

THC vs CBD

When talking about cannabis/ hemp, it’s important to know the difference between these two key cannabinoids.

Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) is one of at least 113 cannabinoids identified in cannabis. THC is the principal psychoactive constituent of the plant and is what causes the “high” feeling that people describe when using certain varieties of cannabis.

Cannabidiol (CBD) is a non- psychoactive cannabinoid. As of 2018, preliminary clinical research on cannabidiol included studies of anxiety, cognition, movement disorders, and pain. Although hemp is low in THC, it typically has higher levels of CBD.